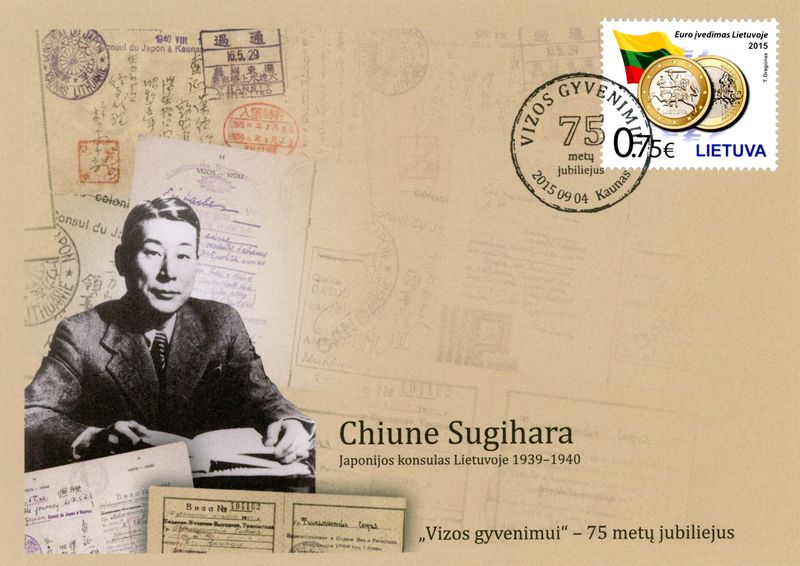

Chiune Sugihara

Of all the stories related to Lithuania and Japan, the story of Chiune Sugihara is most notable and acknowledged. The Japanese consul lived in Kaunas with his family from 1939 to 1940. At the time, Kaunas was the temporary capital of the Republic of Lithuania. After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 and the occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany, many persecuted Jewish refugees fled to Lithuania. As the war moved further east, the Jews were desperate to migrate from Lithuania, which provided a temporary asylum. Although Ch. Sugihara did not receive explicit permission from his government, he issued more than 2,000 Visas for Life in July-August 1940. This way, he saved thousands of people who eventually found their new homelands in the USA, Israel, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and elsewhere. Ch. Sugihara was not the only one who helped Jews in Kaunas. British Consul Thomas Preston and the Dutch Interim Consul Jan Zwartendijk helped to assist the refugees as well.

(Yad Vashem archive)

Biography of Sugihara

Although Chiune Sugihara was born in a remote mountain valley of Japan on the first day of the 20th century (according to the Western calendar), life brought him to many countries all over the world, including Lithuania, where he lived for one year. Despite a short period of residence, one of the most important events of his life took place here – issuing of Visas for Life. During the most challenging period of his life, Ch. Sugihara managed to be a diplomat, an intelligence officer, a businessman, and a family man.

(click on the dates to see more information)

-

Born in Gifu Prefecture on the 1st of January 1900

Sugihara was born in the upland of Japan, Gifu Prefecture. He spent most of his young days in Nagoya, where he graduated from Zuiryo High School in 1917.

-

Entered Waseda University in 1918

Entered Waseda University in 1918His father hoped his son would become a doctor, but Sugihara felt the vocation for languages. After entering the prestigious Waseda University in Tokyo, he studied English but did not graduate.

(Waseda university archive)

-

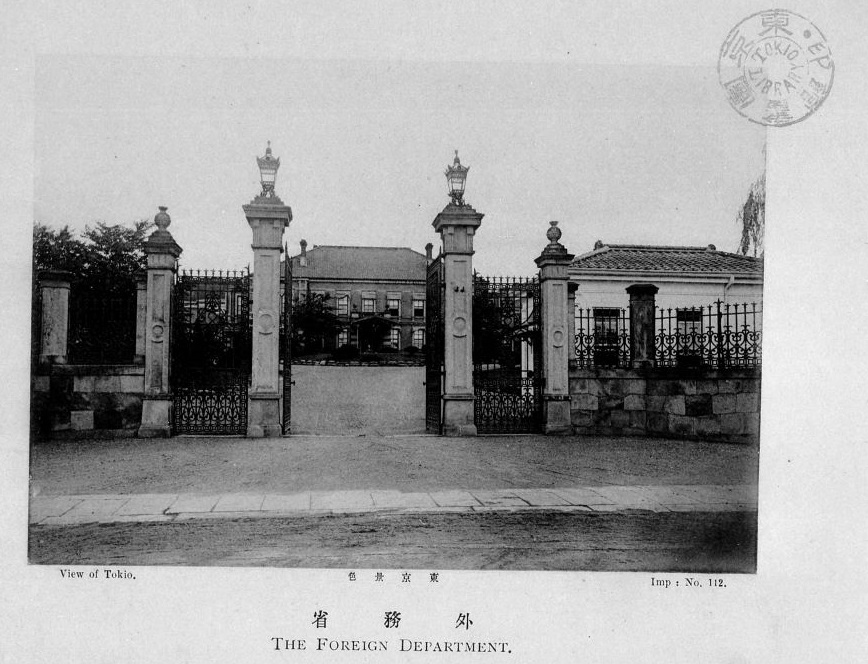

Began working for the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and was sent to Harbin in 1919

Began working for the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and was sent to Harbin in 1919After successfully passing public service examinations, Sugihara started working at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Soon after, he was sent to Harbin City (part of the Republic of China at that time) to study Russian.

(Harbin city during the interwar period)

-

In 1924, married for the first time

Fascinated by the old, classical Russian culture, he embraced the Provoslav faith and married Russian Claudia Semionova in 1924. However the marriage was not long lasting as they divorced in 1935.

-

In 1932, began working as a diplomat in Harbin

In 1932, began working as a diplomat in HarbinHarbin became the capital of Manchukuo, which, at the time, was a newly established puppet state founded by Japan. In the same year, Sugihara began working as a diplomat at the Japanese consulate in Harbin.

(Harbin city during the interwar period)

-

In 1935, returned to Japan

In 1935, returned to JapanWhile living in Manchukuo, Sugihara was disappointed by Japan’s expansionist policies, therefore, resigned from the position in Harbine and returned to Tokyo, Japan. Here, in 1936, married Yukiko Kikuchi. Their first son, Hiroki, was born in Autumn.

(Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs during the interwar period; National Diet Library archive)

-

In 1937, appointed to Helsinki

In 1937, he was appointed to serve in the Japanese diplomatic mission in Helsinki. The second son, Chiaki, was born in Finland, in autumn of 1938.

-

In 1939, arrived in Kaunas

In 1939, arrived in KaunasAt the end of the summer of 1939, Sugihara was appointed to Kaunas, the temporary capital of Lithuania. At the time of the rising outbreak of World War II, the Japanese consulate in Kaunas was convenient to follow the events in the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Sugihara was a well-suited candidate for this position due to his fluency in Russian.

-

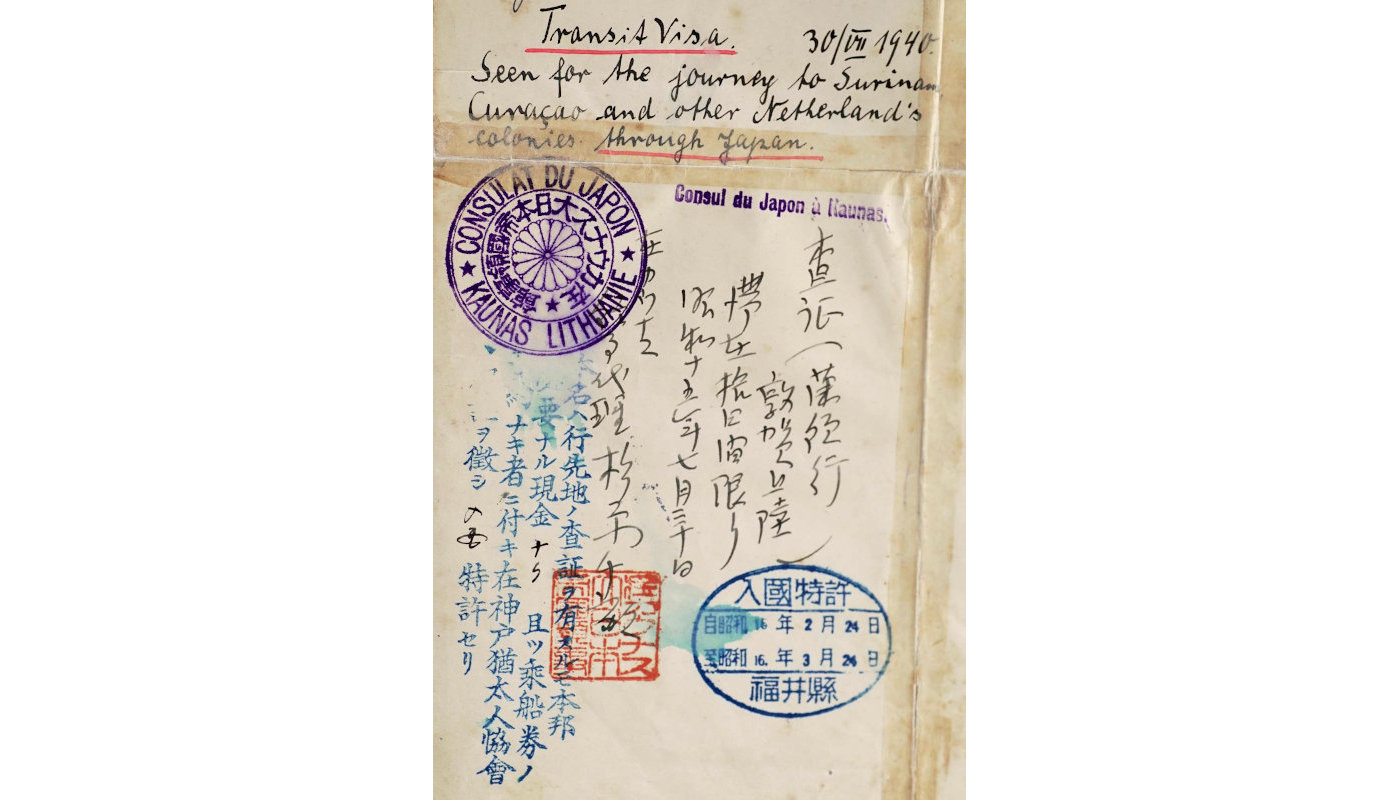

In July-August of 1940, started issuing Visas for Life

In July-August of 1940, started issuing Visas for LifeIn just over a month, Sugihara issued more than 2,000 visas to Jewish refugees who had fled to Lithuania.

In September 1940, departed from KaunasIn the autumn of 1940, Sugihara was forced to leave Kaunas. He ended up in an internment camp in Bucharest, where he lived until the end of the war.

(Yad Vashem archive)

-

In 1947, returned to Japan

Shortly after returning to Japan, Sugihara was asked to resign from the diplomatic service in the ministry.

-

In 1960, got a job in a business enterprise

Due to his fluency in the Russian language, Sugihara got employed in a Japanese company trading with the Soviet Union. Until 1978, he often traveled to Moscow and lived there for some time.

-

In 1980, moved to Kamakura

In 1980, moved to KamakuraSugihara and his family moved to Kamakura at the end of his life.

(Sugihara in his home in Kamakura, 1985; USHMM archive)

-

In 1985, received the Yad Vashem Award

In 1985, received the Yad Vashem Award -

Died in Kamakura, in 1986

Died in Kamakura, in 1986Sugihara died on the 31st of September, 1986 in Kamakura and was buried in Kamakura Cemetery.

(Sugihara's grave)

私に頼ってくる人々を見捨てるわけにはいかない。でなければ私は神に背く杉原 千畝

I cannot forsake those people who come to me for help. If I did, I would be disobeying God.– Chiune Sugihara

Sugihara in Kaunas

One year spent in Kaunas during which Chiune Sugihara performed the heroic deed of issuing Visas for Life became the most notable year in his biography. The reasons why he was appointed to Kaunas in 1939 were clear. Lithuania, an independent state that maintained friendly ties with Japan and shared borders both with the Soviet Union and the Third Reich, was an ideal place to observe events in Europe. The time spent in Kaunas showed that Sugihara stood out not only as a great intelligence officer and diplomat but also as a person who chose the path of humanism. Even though the cult of power prevailed in Europe and the entire world, Sugihara was determined to issue Visas for Life to thousands of refugees.

Japan did not have a consulate building before Sugihara arrived in Kaunas, thus, he stayed at the Metropolis Hotel. As soon as he arrived to Lithuania, on the 1st of September, Nazi Germany invaded Poland and initiated World War II.

(Kaunas railway station, 1925; O. Vitkauskytė's bookstore archive)

The building belonging to Tomkunas in Žaliakalnis was leased to the Consulate. The consulate administration was established on the ground floor, and the Sugihara family lived on the first.

(Lease agreement; Japan Diplomatic Archive / K. Jakubsonas)

Sugihara was the first and only Japanese diplomat in the independent Republic of Lithuania.

(Japan Diplomatic Archive / K. Jakubsonas)

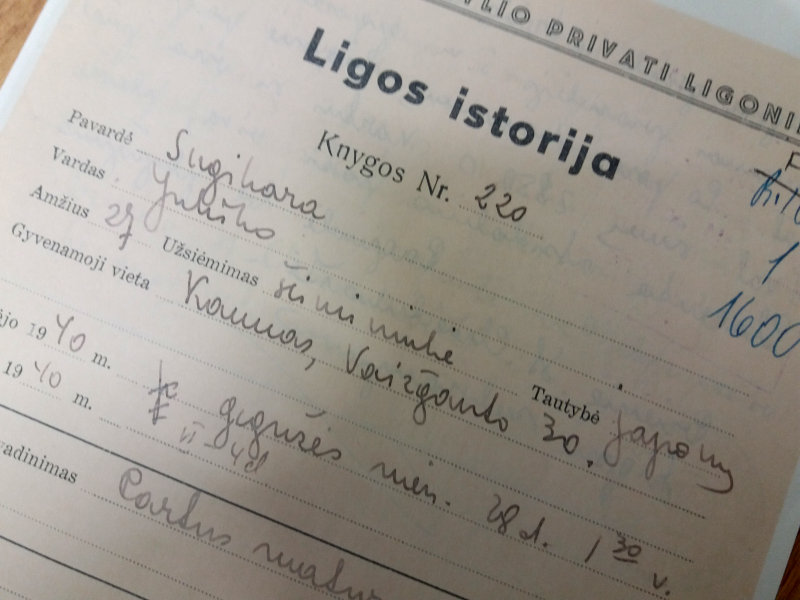

Yukiko Sugihara gave birth to her third son in the prestigious maternity hospital "Mažylis" on Putvinskio street.

(Acceptance to Pranas Mažylis maternity hospital)

On the morning of that day, the Sugihara family saw Jewish refugees gathered near the consulate building asking for Japanese transit visas. Their number was growing.

(Yad Vashem archive)

Sugihara applied to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for permission to issue visas. However, the Ministry raised two conditions: refugees cannot stay in Japan and must have their final destination; refugees must have enough money to survive in Japan. By far, not all applicants could meet the second condition.

(Telegram to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Japan Diplomatic Archive / K. Jakubsonas)

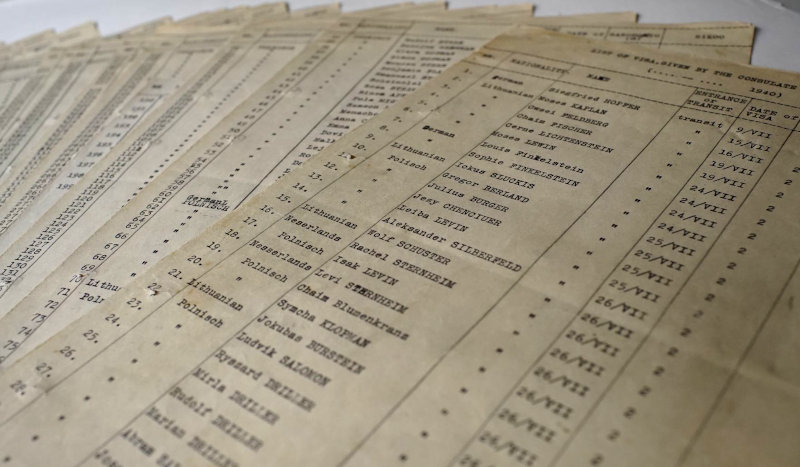

Realizing that human life is the most valuable thing, Sugihara announced that he will issue transit visas to everyone who needs it.

(List of Visas for Life; Japan Diplomatic Archive / K. Jakubsonas)

When Lithuania was incorporated in the structure of the Soviet Union, all foreign diplomatic missions in Kaunas were closed, including the Japanese consulate.

(Metropolis hotel; M. K. Čiurlionis Art Gallery archive)

(Kaunas railway station, ca. 1918)

私のしたことは外交官としては間違ったことだったかもしれない しかし、私には頼ってきた何千人もの人を 見殺しにすることはできなかった そして、それは正しい行動だった杉原 千畝

What I did as a diplomat <...> may have been wrong, but I could not in good conscience, ignore the pleas of thousands of people who sought my help. Therefore, I conclude that I did the right thing.– Chiune Sugihara

The fate of the rescued ones

(Refugees leaving Japan; Yad Vashem archive)

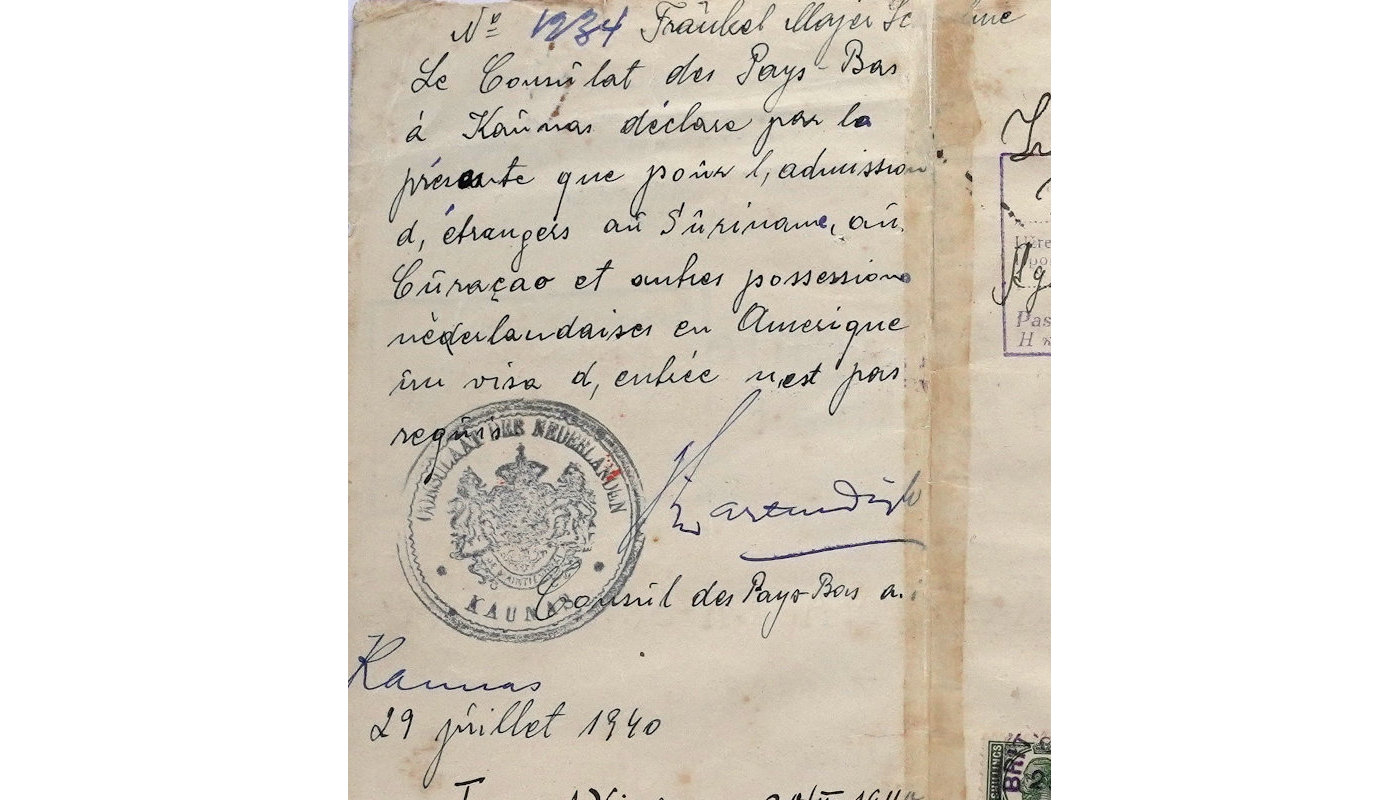

Although Visas for Life are primarily associated with Sugihara’s personality, many other great people and institutions contributed to the success of this story. The visas issued by Sugihara in Kaunas were transit ones, allowing refugees to stay in Japan temporarily. Fictitious visas for the final destination were provided by Jan Zwartendijk, the Dutch consul in Kaunas. Thomas Preston, the British consul in Kaunas, was issuing visas on behalf of occupied Poland for those who did not have passports. After a long journey by the Siberian railway, the refugees were assisted by the Consul General of Japan in Vladivostok Nei Saburo. Upon arrival in Japan, native people and the Jewish community in Tsuruga, Kobe, and Yokohama were taking care of the refugees. Tadeusz Romer, the former Polish Ambassador to Tokyo, also contributed a lot.

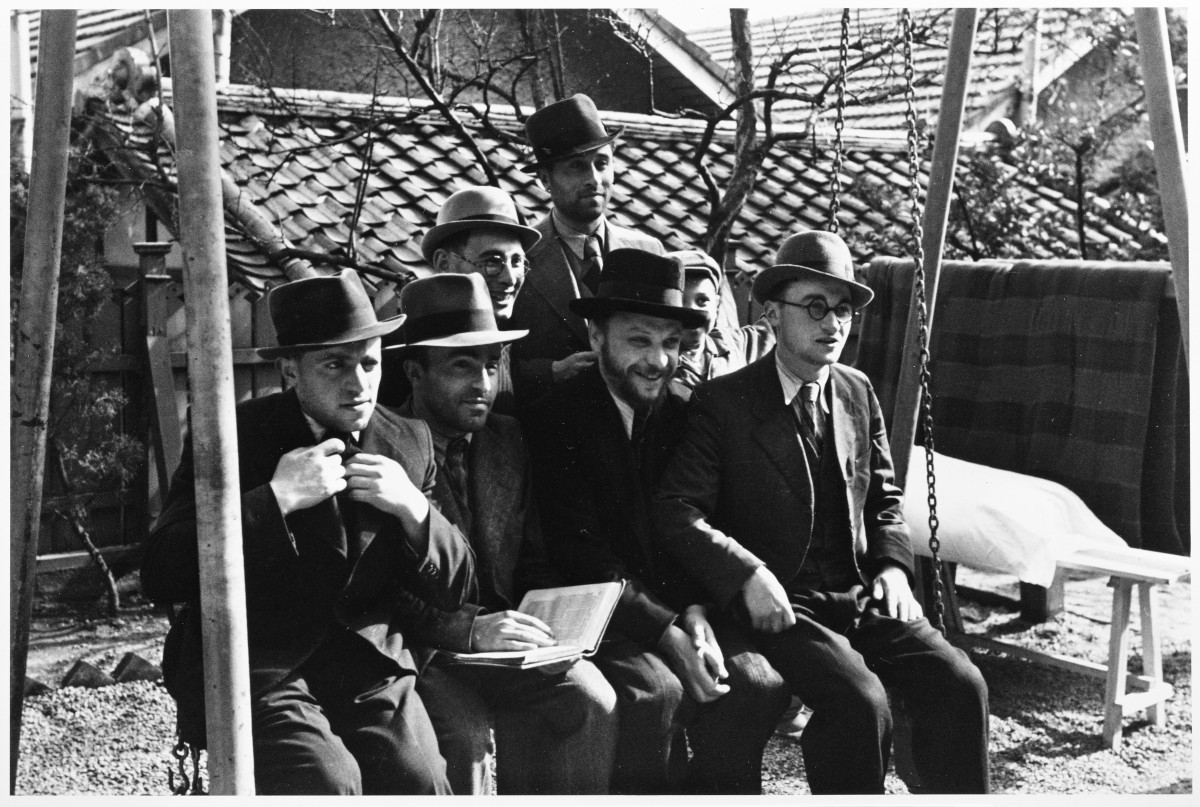

(Jewish refugees in Lithuania, 1939-40; M. K. Čiurlionis Art Gallery archive)

Rescuers

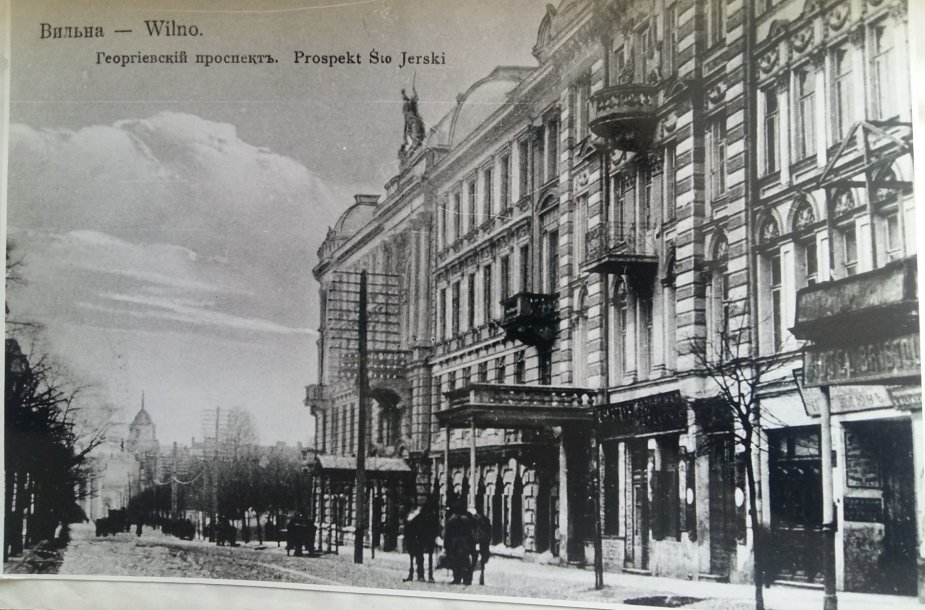

In 1939, the diplomatic institutions of Lithuania were located in its temporary capital Kaunas. The Polish refugees had to obtain transit visas in order to enter Lithuania. The consulate of the Republic of Lithuania which operated in 1939 in Vilnius (then part of Poland) helped refugees to reach Kaunas. Its consul at that time was Dr. Antanas Trimakas.

(Žorž hotel in Vilnius where Lithuania's General Consulate was located; Vilnius Region State Archive)

In 1940, Sir Thomas Preston provided the Jews with around 1200 legal travel certificates that helped them to escape the Holocaust through Japan or Sweden.

He also issued illegal Palestine certificates for the Jews to enable them to escape through Istanbul to Palestine.

(Lithuanian Central State Archives)

In July 1940, Jan Zwartendijk issued 2,345 "Visas to Curaçao" that served the refugees as visas to their final destination. However, none of the refugees actually reached that island.

(USHMM archive)

Despite the restrictions by the Ministry, the acting consul general Mr. Nei Saburo decided to permit the refugees to enter Japan and even issued visas for those who did not have them. The refugees then took the Amakusa-maru ship, managed by JTB, to reach Tsuruga, Japan.

(Nei Saburo Memorial Association)

Ambassador Tadeusz Romer worked in order to provide refugees with the funds necessary for everyday life. Thanks to his negotiations with the diplomats of the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia, and other countries in Japan, he could guarantee the Polish refugees the right to reach their new homelands.

(Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe)

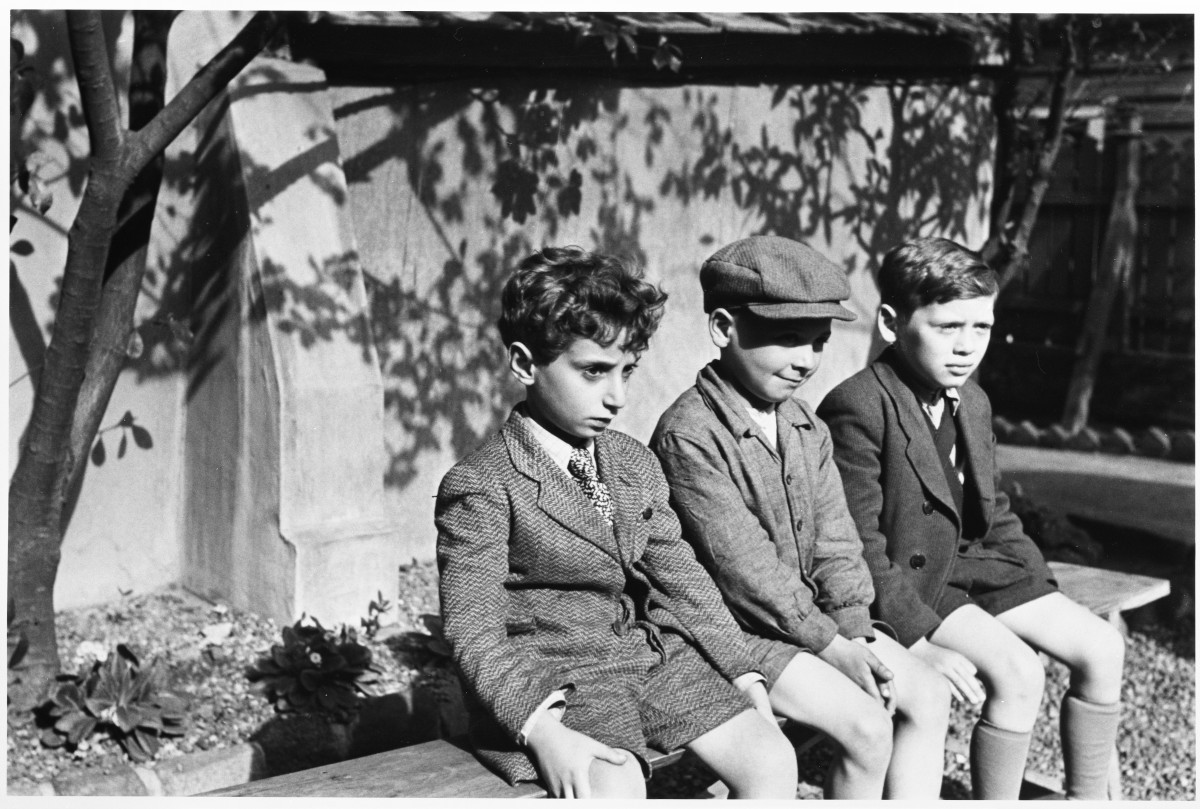

Jewish refugees in Kobe

Tsuruga was the first port in Japan where refugees disembarked. From there they moved to the city of Kobe, which had the largest Jewish community in Japan. Jews spent up to a year in Kobe looking for opportunities to migrate to other countries.

(Osaka Nakanoshima Art Museum archive)

Survivor Zorah Warhaftig

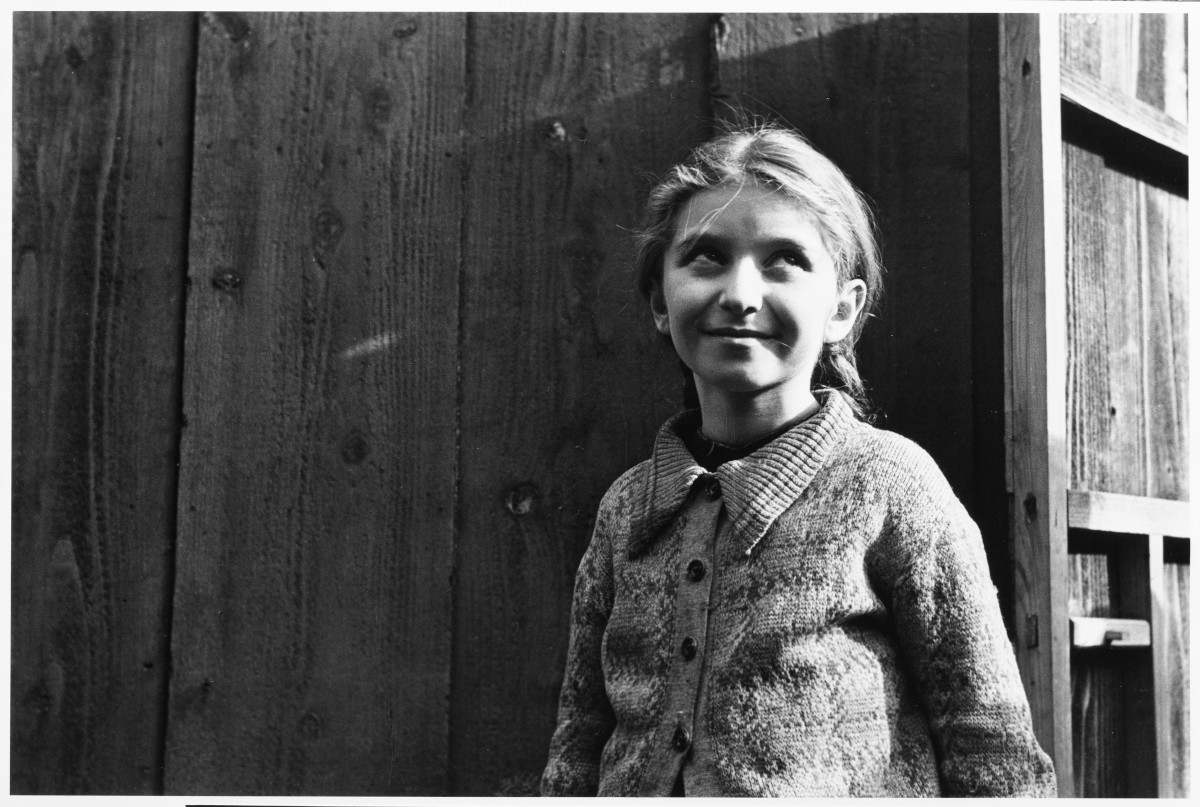

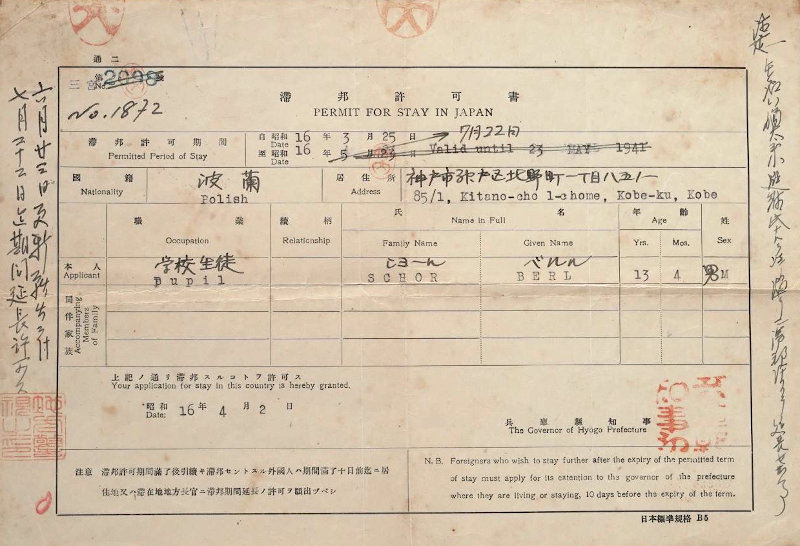

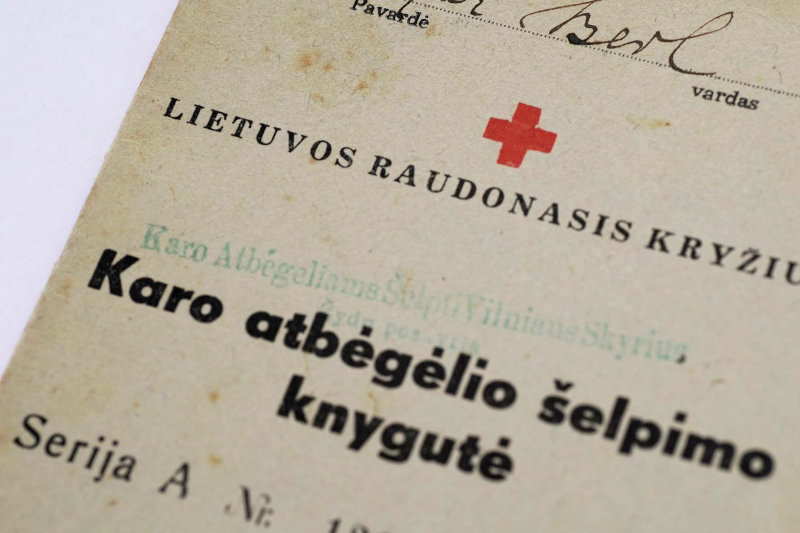

Survivor Berl Schor

The survivor Zorach Warhaftig was one of the leaders of the Polish Jews, who became a refugee when the war broke out and migrated from Warsaw to Kaunas. In 1940, he ensured that refugees in Kaunas would receive all the necessary documentation and successfully migrate. Visa for Life helped him reach Palestine, where he participated in the establishment of the State of Israel. In 1961, he was appointed to the Minister of Religions. You can get acquainted with his family’s salvation story from an interview with his son Emanuel Warhaftig.

Visas for Life gave the foundation for thousands of stories about the survivors. Here you can hear one of them, narrated by Berl Schor, who was 14-years-old in 1940.

(Personal archive of Berl Schor)

Memory of Sugihara

(Sugihara House in Kaunas; Adam Jones, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The rescued refugees remembered Sugihara's feat, and one of them, J. Nishri, finally reached him out in Moscow in 1968. Sugihara visited Israel, and in 1985, just before his death, received the Yad Vashem Award and was honored as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. After his death, on the 27th of October 1993, Sugihara was awarded the Cross of Salvation (lit. Žūvančiųjų gelbėjimo kryžius) in Lithuania.

The history of Sugihara is conveyed in various forms: books, movies, performances, and musical compositions. In recent decades, new places of remembrance are emerging in different countries, including Lithuania, Japan, Israel, the USA, etc., inviting us to remember the history of Visas for Life, which remains relevant in our time.

Places of Sugihara's commemoration

(photos from Tsuruga Museum, Sugihara House, Office of the President of the Republic of Lithuania; Azija LT archives)